CCF Book Club: Lee Kwan Yew

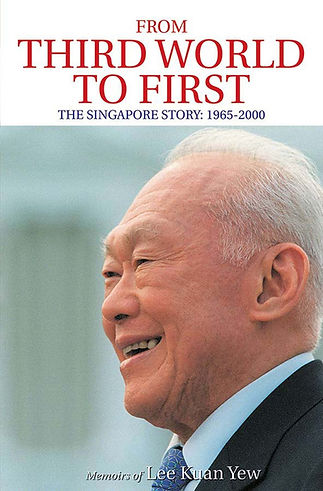

The first ISCSC Book Club was launched in September 2024 with the book From Third World to First (2000) suggested by Professor Bonnie Lee, University of Lethbridge, Canada. The book was written by Singapore founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew. This voluminous memoir (752 pages) revealing the mindset, assessments and strategies of this successful statesman read like a novel. The cast of characters consisted of men in Lee Kuan Yew's administration and colourful statesmen around the world from the 1960s-1980s as Singapore navigated its many internal crises and found its place on the world stage.

To cover this vast canvas, we met for four sessions on Zoom from September 2024 to February 2025 with a lively group of participants from North America, East and Southeast Asia.

How Singapore Did It: Key Points of From Third World to First: The Singapore Story – 1965 to 2000 by Lee Kuan Yew.

Summary by Dr. Joseph Drew, Professor at University of Maryland Global Campus, Washington DC.

This significant book outlines the mechanisms that catapulted Singapore over the years from 1965 to 2000, as it moved from a Third World country not given much chance for worldly success upon independence, to the status of a world economic giant. How did this happen?

In brief, while there were the potential foundations in place for economic and social success, including a can-do spirit and national vigor, responsibility for the actual transition falls almost singlehandedly upon the shoulders -- and on the moral and intellectual strengths -- of the charismatic leader who oversaw the transition, Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew.

This founder, who organized the People’s Action Party in November of 1954, long before independence, as socialist but anti-communist, thought that communist disruption would likely fail in Malaysia but that in Singapore economic success for all would be possible. Thus, his new party was first oriented to fighting against British rule and then to battling against the destruction championed by the communists.

To achieve the party’s goals, camaraderie among the leaders of the PAP was crucial. Most importantly, among the party leadership there was an urgent desire to change an unfair and an unjust society, as Singapore had been while a colony, for the better.

Prime Minister Lee also knew that Singapore was among the lands which already had in place the cultural preconditions for democracy. He also believed that a country needed discipline even more than it did democracy. Plus, as a manager of government, he saw to it that the best people would be recruited to serve the nation; he writes, on Page 664, rather modestly: “the single decisive factor that made for Singapore’s development was the ability of its ministers and the high quality of the civil servants who supported them.”

How to find such people, men, and women whose most important personal possession was character and who would be supremely able to do the job? Lee says that to recruit the best, it was necessary to look at one’s “currently estimated potential” – a person’s power of analysis, imagination, and sense of reality.